Community Spotlights

In this section, we spotlight faculty, students, and organizations across Rutgers-New Brunswick who are doing exciting work around race and liberation.

Deborah Gray White

Board of Governors Distinguished Professor of History

Rutgers University-New Brunswick

Written by Brendane A. Tynes

When I began researching Black women’s affective lives and their forms of resistance for my dissertation, I wanted sources that would help me draw connections between enslaved African women’s practices and Black American women’s practices in the afterlife of chattel slavery. I longed for sources that positioned Black women as subjects and/or agents of history rather than simply as objects or collateral to Black men’s struggle for freedom. Professor Deborah Gray White’s “Too Heavy a Load”: Black Women in Defense of Themselves (1999) (among others) helped provide the foundation for my study. After finishing the book, I wanted to learn more about her, her work, and how her work transformed how we study enslaved Black women.

Growing up as a girl in New York City, White knew that she wanted to study history. She excelled in the subject throughout grade school, so she decided to study history at Binghamton College. There, she explored the discipline’s canon, noting how few assigned texts even discussed Black women’s experiences. Those that did always sutured Black women’s lives to those of the men who possessed them. In historical accounts, Black women were not major characters. They merely moved the plot along for everyone else. After encountering texts by historians and sociologists whose “veiled hostility towards Black women seemed to jump off every page”, White decided to undergo the study of history differently, bringing Black women to the forefront in ways that recognized their labor with respect.

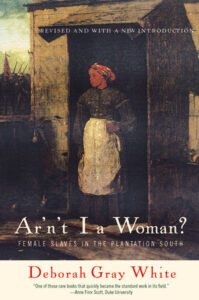

This was no easy feat. White had no models for studying enslaved African women’s experiences, particularly in the way that she wanted to do it. She discovered that the discipline’s value of objectivity was an obstacle to telling Black women’s history. She had to invent a new historical method in order to produce a new subject of history, a position Black enslaved women had never heldbefore. In order to do this, she could not rely on traditional sources about plantation life; diaries, newspapers and journals, slave narratives, plantation records, and other more traditional historical documents could not elucidate the historical subject who was “everywhere but nowhere.” She had to use the accounts of the former enslaved gathered through the Work Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project as data for her dissertation, which would later become her first book Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (1985). Ar’n’t I a Woman became the first full-length published study of enslaved Black women. In Telling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower (2008), White notes that the book was so unique that the Library of Congress had to establish a new category under which to classify it–”women slaves.”

Reflecting upon the impact of her ovarian, discipline-defining book, White described the struggle of integrating history and transforming historiography. Because she wrote one of the first manuscripts centering Black female slaves’ lives and resistance in the United States, White experienced unprecedented misogynoir–a pernicious, pervasive form of anti-black sexism that affects Black women. Every step of the way, she encountered racism and sexism from colleagues, publishers, and others that could’ve ended her career as a historian, and yet she persevered.

Over the last few decades, White has done incredible work for the Rutgers community and beyond. One of her most recent contributions to date has been co-directing the Scarlet and Black research project with Marisa Fuentes from 2016-2021. This research project examined the connections between the Transatlantic Slave Trade and institutions across New Jersey, including Rutgers University. Covering hundreds of years, the research project’s 3 volumes comprise a study of how anti-black institutions, Black life and death, and Black resistance have shifted over time.

With over fifty years of antiracist work in the academy, Professor Deborah Gray White serves as a model for scholarship and praxis. While reading her reflections on her journey, I resonated with her fortitude and sense of purpose; I admired her tenacity. As a Black woman who chooses to write about the experiences of Black women and queer and trans people, I am all too familiar with the constant questioning of how and why I do my work. I was often told that I could not be “objective” because I was studying myself. I too received criticism on the “validity” of my sources with the feedback most often being that I needed to incorporate Black cis men’s and non-black people’s (often misogynist, homophobic, and transphobic) writing about Black gender marginalized people. Rather than decenter my interlocutors, I had to create space for my kind of anthropological study regardless of others’ expectations. White’s work helped establish a cadre of scholarship that forms the containers and contours of that space. I am indebted to her perseverance and innovation; my work is a part of her legacy.